In 2022, the Moon Creek Corporation board of directors appointed two members to begin the ardent task of creating the first Tribal Historic Preservation Office. As a non federally recognized tribe, our task is difficult but possible.

The advisory council on historic preservation provided guidance for federal agencies regarding engagement with non federally recognized tribes in the Section 106 process. Please note the following:

“Non-federally recognized tribes may be invited by federal agencies to participate in the Section 106 process as parties with demonstrated interests in projects or they may seek to participate through collaboration with federally recognized Indian tribes already engaged in the process.”

Section 106 Process: Non Federally Recognized Tribes

- In carrying out Section 106, a federal agency may invite state-recognized tribes or tribes with neither federal nor state recognition to participate in the review process as “additional consulting parties” based on a “demonstrated interest” in an undertaking’s effects on historic properties. Source: 36 CFR 800.2 ( c ) (5) and 800.3 (f ) (3)

- Non-federally recognized tribes can also facilitate their involvement in the Section 106 process a number of ways. In addition to ensuring that all federal agencies know the tribe’s areas of interest (areas where the tribe has had a presence over time), SHPOs and Indian tribes could keep a non-federally recognized tribe informed of projects being undertaken by federal agencies. Non-federally recognized tribes can also delegate a representative (similar to a THPO) as a primary point of contact for historic preservation, who can develop relationships and maintain contact with federal agencies.

- Lastly, we are American Citizens and entitled to the same considerations all citizens have in the Section 106 process.

Dawes Act and Homesteading 1862

This allowed the federal government to break up tribal lands further. Only those families who accepted an allotment of land could become United States Citizens. The Dawes Act designated 160 acres of farmland or 320 acres of grazing land to the head of each Native American Family.

The Homestead Act increased the number of people in the western United States. Most tribes found themselves pushed farther from their homelands or crowded onto reservations. With mixed reactions, some looked for new opportunities, and many hoped to adapt. While others fought to hold onto their traditional ways of life. While the numbers of settlers increased, the land our ancestors knew changed.

- Water was redirected

- Unsustainable farming methods increased

- Native plant diversity dwindled

- fences were built

Redwood Creek Watershed Landowners in 2023

- Green Diamond Resource Company

- Barnum Timber Company – See Barnum Timber Co. v EPA

- R.H. Emmerson & Son

- Six River National Forest – U.S Forest Service

- Others..

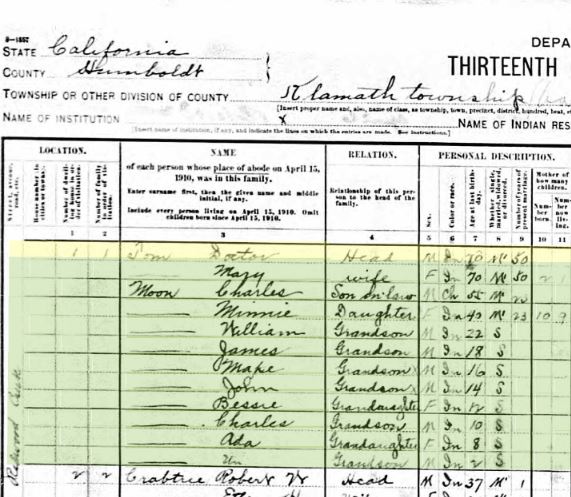

Redwood Creek Ancestry : Redwood Creek Doctor Tom

Know to many as “Redwood Tom”, Doctor Tom was born in 1840. His wife was Mary Tom of Redwood Creek. Both full blood redwood people. He was a blind medicine man. Doctor Tom and Mary couldn’t not read or speak English and only spoke their native tongue. They had two children and only one that was living at the time of their interview.

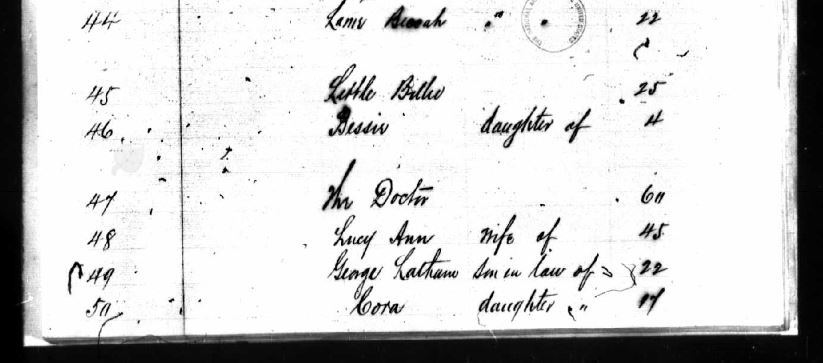

Hupa Ancestry: Old Doctor and Lucy Ann

George Latham Sr. married Cora, the daughter of Mr. Doctor and Lucy Ann. The Matilton Ranch first census noted our fourth grandfather in 1850. Together, they had three children, George Latham Jr. , Ella Latham and Marguerite Latham.

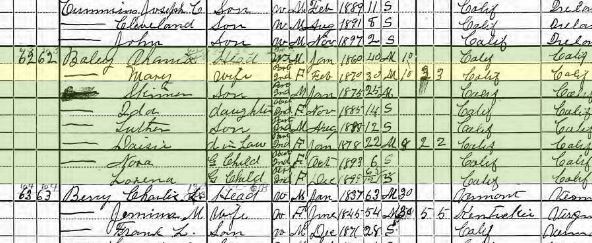

Redwood Acorn Eaters – O’haniel Bailey and Mary

O’haniel Bailey was born January 1860 in Humboldt County California. A well known and documented interpreter for ethnographers, and A.L. Kroeber. He was a well known Whilkut interpreter, and sheared many sheep in the Redwood Creek Watershed, and Bald Hills. His wife was Mary. He was classified as White, but he was half Whilkut. Together they gave birth to six children. One being our great great grandfather, Luther Bailey.